When I first started developing symptoms of PTSD, it was all very confusing. The main emotion that came up for me was sadness. However, it was not a normal sadness, it was a supercharged sadness. It comes up with an intensity that is difficult to describe unless you have experienced it.

What I truly couldn’t understand at the time, were why these emotions kept on coming up. It seemed any small emotion, thought, sound or even the way someone would talk to me would trigger it. I had no control over my emotions and it was extremely unsettling. I would also get intrusive memories and thoughts. I might be having a great day, then all of a sudden memories of the bad calls would surface and suck all the happiness out of me. Sometimes the intrusion is an image, sometimes it is an emotion, other times it involves sounds or smells, sometimes a scene would re-play and I would be re-living what had happened. I would get sucked into the past. Needless to say, staying in the present was extremely challenging.

The lack of control, the lack of understanding of what was happening, and the inability to find a solution was what was most troubling for me with PTSD. Thankfully through counselling, reading books, and some research into trauma and the brain helped me better understand what was happening to my body and mind. In fact, what I learned was completely fascinating (mind you I am a bit of a nerd 😉 ).

Understanding the psychophysiology of trauma and memory was a major stepping stone for me. When what I was experiencing started to make sense, I felt a sense of autonomy and control again, I knew I wasn’t going crazy. This knowledge didn’t make having a flashback or getting triggered less painful or prevent them from coming up, but suddenly things were a bit less scary.

One way to look at PTSD is to see PTSD as your body’s way of adapting and protecting you from traumatic experiences. However, your brain’s method of protection can result in memory consolidation problems. Normally memories are experienced and processed into long-term storage by an area of our brain called the hippocampus. This memory consolidation can occur during waking hours but the majority of the work occurs during REM sleep and trauma can cause a disturbance to this memory consolidation process (Marle, 2015).

To help us better understand memory consolidation, let us delve a little into the anatomy and physiology of the brain.

Anatomy – The Triune Brain

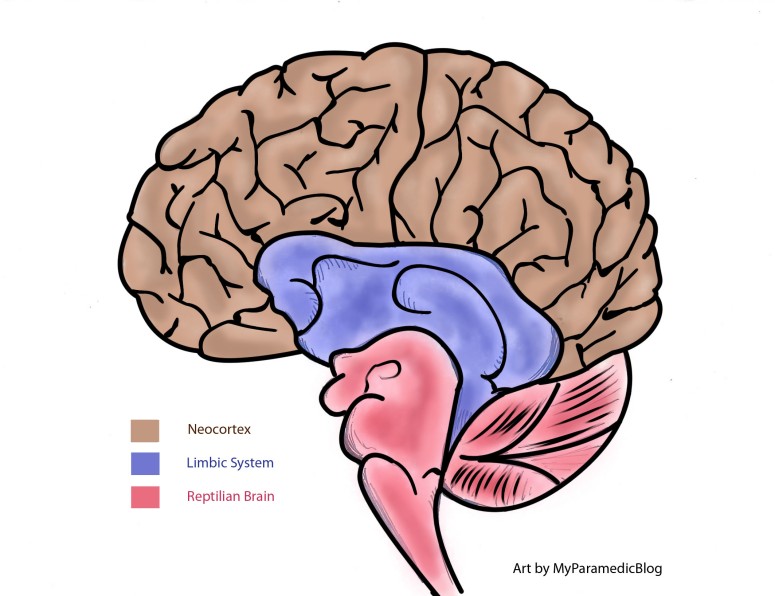

The brain can be classified into three layers: The reptilian brain, the limbic system or mammalian brain (also known as the emotional brain), and the neocortex.

Reptilian brain

The oldest part of our brain is the reptilian brain, it maintains basic bodily functions such as vital signs (heart rate, breathing, blood pressure, temperature, balance, etc), sleep-wake cycles, hunger, arousal, chemical balances, and is maintained by our unconscious (Media, 2015). The reptilian brain consists of the brainstem and the cerebellum and is reliable but somewhat rigid and compulsive.

The Limbic System (The Emotional Brain)

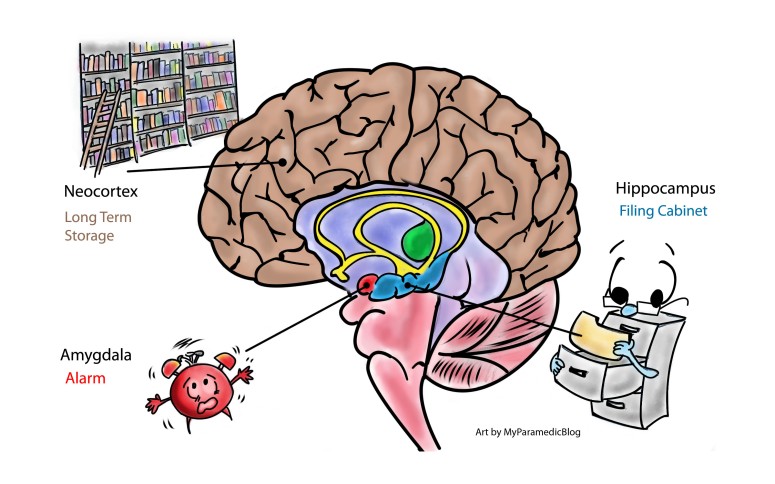

The limbic system, also known as the mammalian brain as it was thought to have emerged in the first mammals. All animals who live in groups and nurture their young have this brain structure (Kolk, 2015). The limbic system is responsible for emotions, recording of memories and behaviours that produce positive or negative experiences such as pain or pleasure, and is involved in categorization and perception (Sapolsky, 2004). In this way, the limbic system has a strong influence on our behaviours and functions at a subconscious level. The main structures of the limbic system consist of the hippocampus, amygdala, and hypothalamus. The key structures to remember in the limbic system in regards to PTSD is the amygdala and the hippocampus. One way to look at it is to view the amygdala as the brain’s alarm system and the hippocampus as the filing cabinet for memory storage (Media, 2015). We will revisit these two structures as we delve into the physiology of PTSD.

The Neocortex (The Rational Brain)

Lastly, the neocortex is what many says, makes us human. It consists of two large cerebral hemisphere that is responsible for the development of language, abstract thoughts, imagination, and consciousness. It is also the core to planning, anticipation, allows you to sense time and context, and is able to inhibit inappropriate actions as well as allowing us to empathize and understand others (Kolk, 2015). It is the neocortex that gives us almost infinite learning abilities, it is flexible and malleable, and is what allowed human cultures to develop. Within the neocortex, we will be primarily focusing on the frontal lobes and more specifically the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) and the medial prefrontal cortex (MPFC).

Trauma and the Brain

So what happens when our brain senses danger? Let’s say you have just returned home and as you walk up the stairs in the corner of your eye you see a giant black mass with eight thin protrusions coming out of it. Immediately your heart starts racing, your eyes dilate, you start breathing quickly and you feel your muscles tense up. Your body immediately halts, freezing in place and you feel ready to run if this thing starts coming at you. It takes you a second to realize it was just a large dust bunny, not a spider, that had collected in the corner of your stairs. You tell yourself how silly that was and you can’t believe you got such a fright from it.

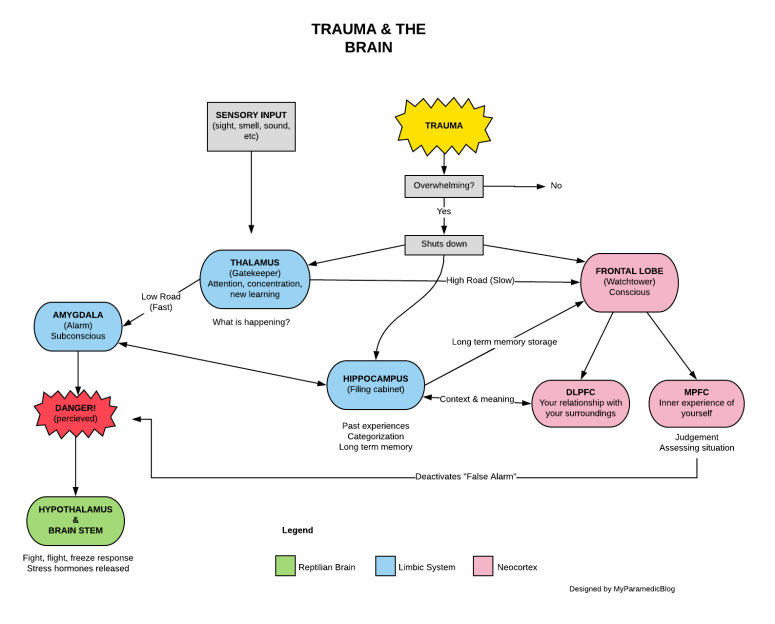

In the above scenario, the primary sensory input of danger is through your eyes, you suddenly see a dark shape that resembles a spider. Sensory input can be transmitted through any of your senses (sight, smell, sound, kinesthetic, touch, etc) and it gets sent to your thalamus. The thalamus integrates information about what is happening, (in this case, a giant black mass with eight thin protrusions), then relays this information to the amygdala (alarm system) and the frontal lobe. The amygdala receives information several milliseconds faster than the frontal lobe, also coined as the “low road” by the neuroscientist Joseph LeDoux (Kolk, 2015). The amygdala quickly interprets the information with feedback from the hippocampus, which relates input from past experiences (shape looks like a spider, so must be a spider), determines the “spider” as a threat, and sets off the alarm (Kolk, 2015). As a result, your hypothalamus and brain stem activates the flight and fight response which makes you tense and freeze, as stress hormones get released throughout your body, causing your heart to race and your breath to quicken (Sapolsky, 2004). It is because the amygdala reacts faster than the frontal lobe, that we often times react to the perceived danger before we are even aware of what is happening.

While the amygdala acts as an alarm system, the frontal lobe acts like a watchtower, it sees the bigger picture of what is happening in the environment around us. Like we discussed earlier however, the frontal lobe which is part of our conscious brain (also coined as the “high road”), is slower than our older survival brain. From an evolutionary perspective, this would make sense, as escaping imminent death by quickly taking action and running is more important than contemplating the scenario and then deciding if running is a good choice (as by then, you may have already become a cougar’s breakfast).

Within the frontal lobe is the DLPFC (dorsolateral prefrontal cortex) and the MPFC (medial prefrontal cortex). It is specifically the MPFC that makes judgements, assesses the situation and allows you to consciously deactivate the alarm (amygdala) if the threat is deemed false (Kolk, 2015). Applying this to the above scenario, because the amygdala reacts faster than your frontal lobe, you immediately feel the fight and flight response (all the physical changes mentioned earlier and the preparation to run) before you realize that the spider-like shape is indeed a dust bunny. Once your frontal lobe has had time to process the bigger picture, that there is, in fact, no spider, you deactivate the alarm and slowly your body returns to homeostasis as your heart rate and breathing drops back to normal and your muscles relax. Next, your hippocampus (filing cabinet) processes what you have learned from this experience, time-tags it, and sends it to your neocortex to be stored as long-term memory (Media, 2015). This is how normal memory is stored.

When someone is exposed to a traumatic event (when a person is overwhelmed by something beyond their control), it has been found that the older parts of your brain (the reptilian brain and limbic system), over-rides the conscious part of the brain (the neocortex) as a survival reflex (Media, 2015). In fact, certain parts of the brain go offline, such as the hippocampus and the thalamus (Kolk, 2015). Since the hippocampus is the filing cabinet for memory storage, when it shuts down it means it can no longer process memory into long-term storage. Instead, the memory is stuck in the limbic system resulting in the formation of traumatic memories (London, 2016). It also means these stuck memories can easily be triggered by the environment (triggers can be anything like sight, sound, colour, smell, etc) causing the alarm to go off again (Media, 2015).

Likewise, your thalamus, which writes your autobiography, also shuts down, which causes memories to be processed into fragments of information and isolated sensory imprints (images, sounds, strong emotions of helplessness, etc) (Marle, 2015). It is this lack of autobiographical context that when triggered, the memory is relived as it is happening in the present, otherwise known as a flashback (Marle, 2015). What is significant is that it isn’t just the limbic system that is affected, other parts of the brain, like Broca’s area and the left cerebral cortex significantly decreases in activity too (Kolk, 2015). Consequently producing the various symptoms PTSD survivors often experience, such as the inability to verbalize what had happened (Broca’s area is involved in speech), and the inability to consciously change how one feels about the event through logic and reasoning (left cerebral cortex is largely involved in logic).

In summary, when a person is exposed to trauma, our body’s natural instinct is to try and protect ourselves. In the process of doing this, our survival brain (older reptilian and limbic system) takes over our rational brain (neocortex). It is important to remember that this is a natural process, it is only when the trauma is so overwhelming that it causes certain parts of our brain to deactivate, like the hippocampus, that it can interrupt memory processing and potentially lead to PTSD.

The truth is, no one is immune to trauma, simply being human and having a highly structured brain makes you vulnerable to trauma. Those who are in professions that are often exposed to violence and death, like first responders and military personnel, increases their risk of occupational stress injury and getting PTSD.

Anyways, I hope you have found this information helpful and I will leave you with this video below, put together by NHS Lanarkshire EVA Services and Media Co-op, which nicely summarizes trauma and the brain:

References

Kolk, B. (2015). The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, mind and body in the healing of trauma. New York, NY: Penguin Books.

London Trauma Specialists (Producer). (2016, April 08). Brain Model of PTSD – Psychoeducation Video [Video file]. Retrieved January 26, 2018, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yb1yBva3Xas

Marle, H. V. (2015). PTSD as a Memory Disorder. European Journal of Psychotraumatology. 6(1), 3. doi:10.3402/ejpt.v6.27633

Media Co-op (Producer). (2015, September 21). Trauma and the Brain [Video file]. Retrieved January 25, 2018, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4-tcKYx24aA&feature=youtu.be

Sapolski, R. M. (2004). Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers. New York, NY: St. Martin’s Press. p.209, 211